Villa of Via dei Bagni Nuova

As part of urbanization works conducted in 2015 in Monfalcone, the remains of three rooms pertaining to a villa were discovered. One of them, which can be interpreted as a reception room, was paved with a valuable white-tiled mosaic carpet bordered by a black-and-white-tiled frame. In the center, the floor was adorned with a polychrome panel with geometric designs.

Within this frame, in a central position, stands a depiction of a chalice from which red and black racemes emerge.

The mosaic dates to the second half of the second century AD, but the room in which it is found and perhaps the entire building probably date to the second half of the previous century.

The discovery of marble slabs and tubules from heating suggest the existence of thermal or otherwise heated environments in one of the life stages of the complex.

Archaeological data allow us to place the abandonment of the villa in a period between the late 3rd century and early 4th century AD.

Villa on Mandrie Street

The building, investigated between 1990 and 1997, consisted of a multi-level main body joined by two lateral structures that opened onto a central courtyard, so that the floor plan took on a U-shape.

Excavations have revealed two phases of building and use of the villa over a period of time from the second half of the first century B.C. to the third century A.D. The dwelling, which on the basis of the building materials used (mosaic tiles, marble slabs, painted plaster, heating pipes, and fragments of glass window panes), must certainly have been a prestigious residence, characterized by residential, productive, and thermal environments, and was probably connected to a small dock.

This also allowed goods and merchandise to arrive by sea.

Archaeological and archaeozoological records indicate that among the economic activities carried out in the rustic part of the villa were those of sheep breeding and wool production.

Columbus Street Villa

Archaeological excavations conducted between 1992 and 1996 brought to light the remains of structures referable to a villa whose rooms developed between the first karst reliefs to the north and the sea. The residential part was characterized by rooms whose floors were decorated with refined mosaics with geometric motifs in black and white; the rooms, located around a courtyard, were probably arranged on terraces at different heights so as to articulate, even scenographically, the building.

In contrast, to the south was an area dedicated to productive activities, a very large basin measuring 20 x 15 meters, which, based on its structural features, has been interpreted as a private dock: there were possibly fish or shellfish breeding facilities here.

A corridor, believed to be a loggia due to the presence of limestone column bases, connected the residential part with the dock.

The villa was built in the second half of the 1st century B.C. and underwent renovation around the middle of the 1st century A.D., at which time the dock was built. The building complex was then permanently abandoned during the 2nd century AD.

Villa at the Marcelliana church

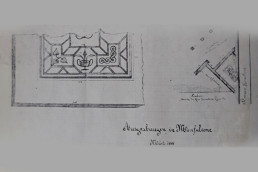

The structures, identified in the late 19th century by Enrico Maionica, are said to refer to several rooms facing a porticoed courtyard. The floor of one of them was decorated by a mosaic with a complex black-and-white geometric pattern datable to the 2nd century AD.

Roman villa in Staranzano: the first investigations

Fortuitously, the discovery of a mosaic floor in the Staranzano area, northeast of the built-up area of the parish church property, occurred.

Prompt reporting by the municipality meant that the Superintendence of Antiquities of the Venezie was able to intervene promptly to view the case. Under the diligent guidance of technical assistant G. Runcio the excavation was started and, by the agreement reached between the municipality the parish church and the neighboring landowner, Mr. E. Laurentic, was able to be expanded to an area of 128 square meters, at a constant depth of 0.80 meters from ground level.

The difficulty of the work was mainly due to the highly clayey soil and the goodness of the wine and fruit crops in the area, which elevated in no small measure the compensation to be paid and owners for the damage suffered.

The interest in the complex that has come to light, however, has afforded the work of the Superintendency the utmost solicitude and understanding on the part of the local authorities, who earnestly desire, to their credit, to be able to highlight and preserve in view what documents the ancient life of the place.

The labor therefore was made available by the City of Staranzano having sent there the Directorate of Excavations of Aquileia a skilled and skilled worker so that supervision over the earthworks would be constant.

Towards the end of May there was also an inspection by the Superintendent of Antiquities himself, Dr. B. Forlati, who was warmly pleased with the work in progress.

From what has now been brought to light, the visitor reports the impression of an interesting and lively Roman-age wall complex in its structures, its orderly topographical arrangement, and the simple elegance of its mosaics. And it is a discovery that is not surprising given the presence a short distance to the west of the Roman road that passed through the lower Monfalcone area, linking Aquileia to Tergeste, and the similar discoveries, of houses and works from the Roman period, that occurred in the area in earlier years.

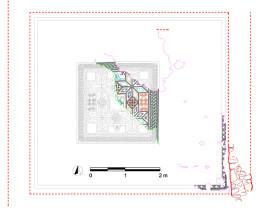

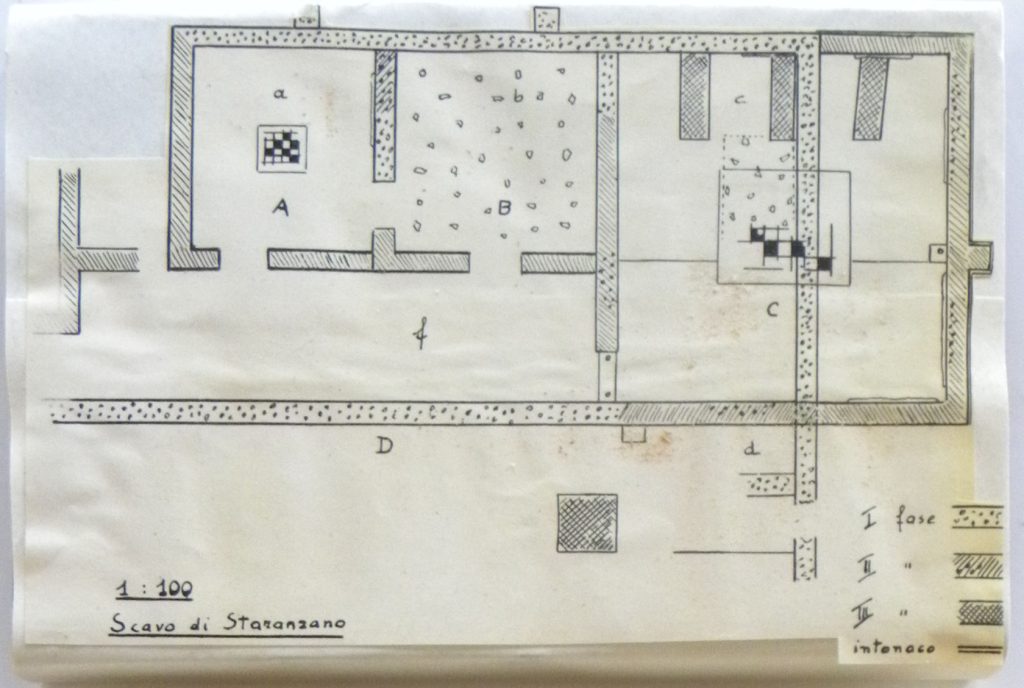

The excavation has currently uncovered the rooms that line the east side of the complex, it would remain to explore the west side with the connecting rooms in the south and north sides whose continuation is evident from the western clay embankment (fig.1).

Le strutture che si elevano dal terreno di base per un’altezza media di circa metri 0,50 si presentano di tre qualità diverse ed aiutano, insieme al livello e al tipo di pavimenti, a seguire la vicenda edilizia della casa. I muri che affiorano a profondità maggiore si presentano a ciottoli di fiume. La sezione normale di tali muretti a corsi regolari dà uno spessore medio di metri 0,45 e dimostra la loro erezione con circa quattro elementi collegati da malta biancastra di poca consistenza. La pianta della casa costruita a muri di ciottoli e in seguito ampliata da sul lato sud di circa quattro metri, ma nella fase prima, di cui ora parliamo, era costituita, nell’area scoperta almeno, poiché i muretti di ciottoli continuano sottoterra tanto verso Nord quanto verso Ovest, da tre vani (a, b, c) che si aprivano nell’interno verso un probabile corridoio (f). Il muro a ciottoli lungo il lato Est presenta all’esterno due piccoli contrafforti dello stesso suo tipo, disposti ad intervallo regolare dello spigolo Sud-Est della casa, rifiniti in modo da far pensare ad una loro funzione decorativa o strutturale connessa al muro perimetrale.

A sostegno, ad esempio, delle gronde di scolo del tetto. L’ampliamento della casa verso meridione con muri di tipo diverso riprende infatti il medesimo motivo del contrafforte sul lato Sud. Si noti che la distanza del contrafforte dallo spigolo a Sud Est è circa la stessa su tutti e due i lati. Questa equidistanza che riprende quella degli elementi aggettanti sul lato Est non può essere casuale (fig.2). L’ampliamento della casa avviene dunque come abbiamo or ora notato con struttura di tipo diverso: si reimpiegano i ciottoli risultanti dalla rovina di alcuni tratti dei muri precedenti e ad essi si aggiungono con poca malta gialliccia, più grassa, frammenti di tegole e mattoni sottili giallo chiari di fine argilla cotta in fornace, mantenendo un spessore medio di metri 0,45.

Rather than in the walls, where tile fragments predominate, bricks are encountered in abundance in the earth being quarried and are likely evidence of the regular brick row structure that the masonry on high ground will have had. It is interesting to note how an attempt is made to give the functional masonry a certain organicity, alternating rows of pebbles with rows of fragmented tiles, according to a rhythm present wherever the nearby river had provided building pebbles for the inhabitants.

See the monumental example offered by Turin's Porta Romana, which alternates between bright red brick and white cobblestones in an extremely painterly cadence.

The exterior of the wall added to the east and south testifies even more validly to the perimeter function of the cobblestone wall to the east and the rearmost wall to the south, as it is more solid than the interior walls and walks on a slightly overhanging base plinth. Also absent all around are attachments of other masonry or traces of pavement battens (fig.3).

Further variations in the internal plan of the complex, again related to the area brought to light, are brought by a third type of masonry, with an average thickness of half a meter built almost only with fragments of tiles joined by little thin, grayish mortar.

Whereas in the walls of the second phase the tile fragments were often arranged in a herringbone pattern with a tasteful decorative sense as well as practicality of use, in these walls of the third phase the tone is that of a structural arrangement that jumbles tiles and bricks with purely functional intent and much haste in execution (fig.4).

Representative of this phase are the three small walls built above the floor of compartment C in the east-west direction and the large quadrangular basement in the area of compartment D so far discovered to the south.

The third phase rather than expansions therefore seems to have brought internal additions resolved with reused material, taken from some old deposit because there are tiles and bricks of various types and stamps found there, prevailing, however, always the light-colored clay fine pulled form of thin thickness.

The most frequent stamps are thus already known in the area from the kilns of Q.CLODIUS AMBROSIUS, not that the more singular ones of B. VETTIA, ASSIANI and L. PET., impressed in the elements with different characters such as to demonstrate the development over time of production. Typical in this regard are the kiln stamps of Q. CLODIUS AMBROSIUS.

Regarding the levels and paving of the compartments we note that compartments B and C connected to and bounded by the older walls, present a beaten earth paving with inserted in picturesque disorder of fragments of beautiful green, gray, and red pebbles along with a few dark red terracotta flakes.

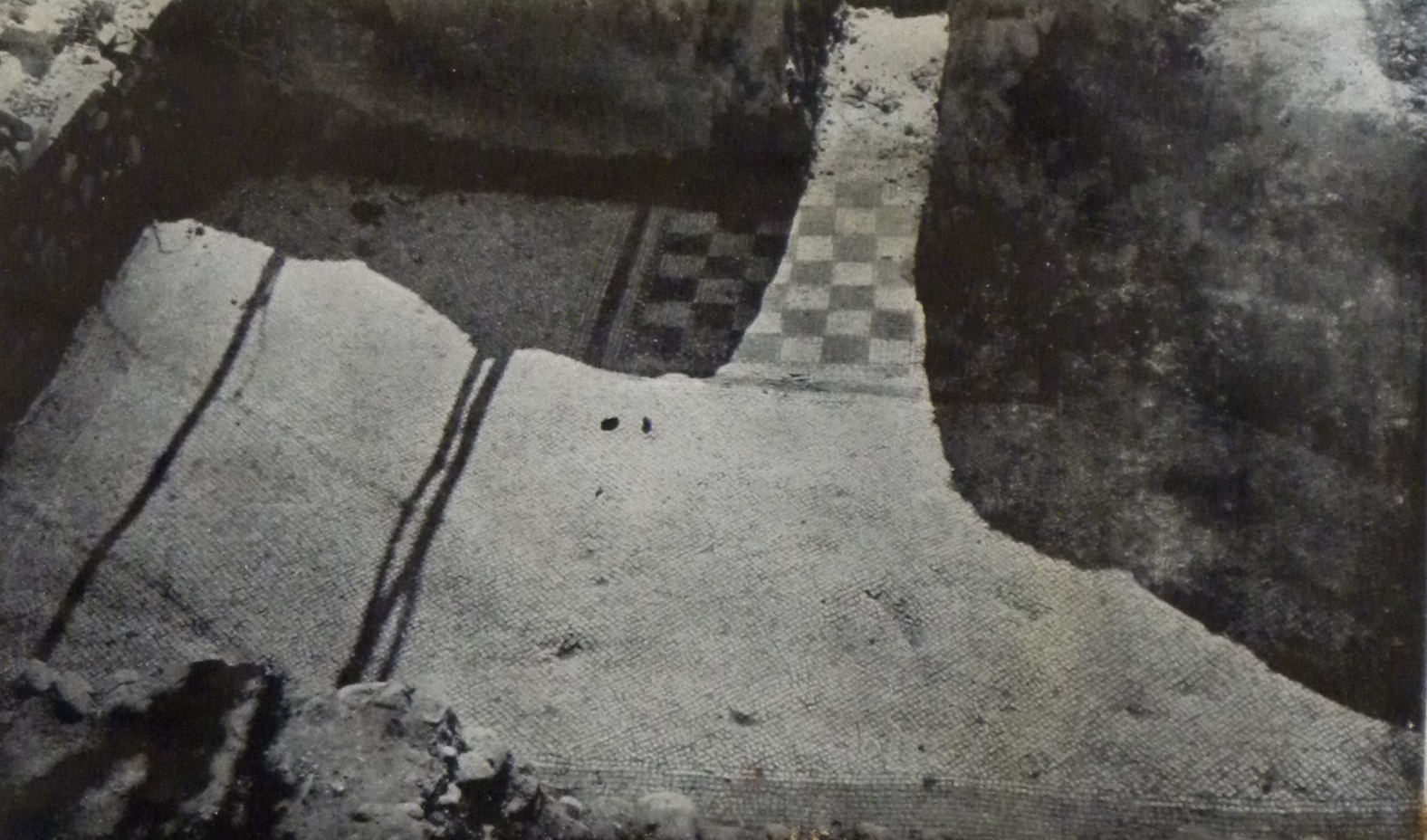

This type of floor, Pliny's classic "signinum," is admirably preserved here in Compartment B and continues to be in use in the later phases, while in Compartment C, which undergoes the expansion of the second phase and the modification of the third, the signinum is covered by the second phase floor of cubed and regular terracotta and regular tessellated bichrome, black-white with a central checkerboard emblem.

Room A is also covered with a similar tessellation with the small checkerboard in the center, while and all the other rooms have uniform and terracotta cube flooring (fig.4).

Il livello dei pavimenti tra la prima e la seconda fase quindi varia di qualche centimetro appena o non varia affatto (fig.5).

A sostegno, ad esempio, delle gronde di scolo del tetto. L’ampliamento della casa verso meridione con muri di tipo diverso riprende infatti il medesimo motivo del contrafforte sul lato Sud. Si noti che la distanza del contrafforte dallo spigolo a Sud Est è circa la stessa su tutti e due i lati. Questa equidistanza che riprende quella degli elementi aggettanti sul lato Est non può essere casuale (fig.2). L’ampliamento della casa avviene dunque come abbiamo or ora notato con struttura di tipo diverso: si reimpiegano i ciottoli risultanti dalla rovina di alcuni tratti dei muri precedenti e ad essi si aggiungono con poca malta gialliccia, più grassa, frammenti di tegole e mattoni sottili giallo chiari di fine argilla cotta in fornace, mantenendo un spessore medio di metri 0,45.

Rather than in the walls, where tile fragments predominate, bricks are encountered in abundance in the earth being quarried and are likely evidence of the regular brick row structure that the masonry on high ground will have had. It is interesting to note how an attempt is made to give the functional masonry a certain organicity, alternating rows of pebbles with rows of fragmented tiles, according to a rhythm present wherever the nearby river had provided building pebbles for the inhabitants.

See the monumental example offered by Turin's Porta Romana, which alternates between bright red brick and white cobblestones in an extremely painterly cadence.

The exterior of the wall added to the east and south testifies even more validly to the perimeter function of the cobblestone wall to the east and the rearmost wall to the south, as it is more solid than the interior walls and walks on a slightly overhanging base plinth. Also absent all around are attachments of other masonry or traces of pavement battens (fig.3).

Further variations in the internal plan of the complex, again related to the area brought to light, are brought by a third type of masonry, with an average thickness of half a meter built almost only with fragments of tiles joined by little thin, grayish mortar.

Whereas in the walls of the second phase the tile fragments were often arranged in a herringbone pattern with a tasteful decorative sense as well as practicality of use, in these walls of the third phase the tone is that of a structural arrangement that jumbles tiles and bricks with purely functional intent and much haste in execution (fig.4).

Representative of this phase are the three small walls built above the floor of compartment C in the east-west direction and the large quadrangular basement in the area of compartment D so far discovered to the south.

The third phase rather than expansions therefore seems to have brought internal additions resolved with reused material, taken from some old deposit because there are tiles and bricks of various types and stamps found there, prevailing, however, always the light-colored clay fine pulled form of thin thickness.

The most frequent stamps are thus already known in the area from the kilns of Q.CLODIUS AMBROSIUS, not that the more singular ones of B. VETTIA, ASSIANI and L. PET., impressed in the elements with different characters such as to demonstrate the development over time of production. Typical in this regard are the kiln stamps of Q. CLODIUS AMBROSIUS.

Regarding the levels and paving of the compartments we note that compartments B and C connected to and bounded by the older walls, present a beaten earth paving with inserted in picturesque disorder of fragments of beautiful green, gray, and red pebbles along with a few dark red terracotta flakes.

This type of floor, Pliny's classic "signinum," is admirably preserved here in Compartment B and continues to be in use in the later phases, while in Compartment C, which undergoes the expansion of the second phase and the modification of the third, the signinum is covered by the second phase floor of cubed and regular terracotta and regular tessellated bichrome, black-white with a central checkerboard emblem.

Room A is also covered with a similar tessellation with the small checkerboard in the center, while and all the other rooms have uniform and terracotta cube flooring (fig.4).

Il livello dei pavimenti tra la prima e la seconda fase quindi varia di qualche centimetro appena o non varia affatto (fig.5).

Interessante è notare i frammenti di intonaco che aderiscono ancora alle pareti est sud e ovest nel vano C e che si fondano sul tessellato pavimentale, dimostrando la precedenza del mosaico nell’ordine dell’esecuzione dei lavori nella casa e la contemporaneità del pavimento in cotto e del tassellato perfettamente suturati (fig 6).

Rare fragments of amphorae and vessels, lacking absolutely any kind of furnishings, the building faintly raises its voice from a single stone inscription.

Like the walls, the stone also shows that it was reworked and engraved in two different periods.

The type and that of a quadrangular platform fragment (57x57x0.90) that on its side bears the epigraph B.D.V. PETICIA LL AR. and on the surface the later inscription NIGELI almost barely graffitied. The stone was found in chamber c together with an in situ anchor without inscription but of roughly similar proportions (59x60x0.09) with a central hole in the surface.

At the current state of the excavation that I simply present here reserving further details when the excavation is completed to avoid errors of evaluation or interpretation so easy on the "surprise" terrain of 'Archaeology, it is possible to deduce the following: we are faced with a building whose origin by types of floor structures can be placed on the border and three first century B.C. and the first century A.D., which develops with extensions in plan and black-white geometric mosaic flooring around the second century A.D., taking on a particular appearance later.

The latter is given to it by the internal modifications that are not very canonical for the life of a simple rural villa, as the primitive appearance of the complex would make us call it typologically. In fact, if room c in its second phase suggests its probable distraction into a triclinium with the terracotta floor in the tricliniar bed area and the mosaic carpet the free area, in the third phase it is oddly divided into four small rooms proceeding above the terracotta floor (see fig. 1).

Why?

E quale è lo scopo del grosso basamento quadrangolare costruito in D pure sopra il pavimento in cotto (fig.7)?

Troppo grande per essere la base di un pilastro o di una colonna, il cubo rimane per ora a sé stante ed aspetta una soluzione nel procedere dello scavo verso Ovest. Ma l’iscrizione trovata apre una possibilità nuova di interpretazione: non potrebbe essere stato adibito ad un certo momento a sacello, a sala di culto privato o pubblico?

They might have been what horrendous description the initials B.D.V were surely read as B(ONAE) D(EAE) V(OTUM), interpreting the stone as the base of an element (labrum?) offered by Peticia, probable freedwoman of a Lucius, surname AR(RIANA?) as a vow to the Bona Dea, a well-known and honored deity of our region (compare the sacellum of Trieste and of the cult in Istria and Aquileia), especially by women precisely if freedwomen.

In this case, the north stone threshold, finished, high, with side holes for the hinges of the door-knockers, nor the special subdivisions of the eastern compartment that might have run as offering deposits or secret recesses of worship (the Bona Dea was often associated with high deities), nor some trace of transenna perhaps recognizable between the terracotta floor tiles and the tessellated, along their always perfect and stringent suture in the northern area, nor the stone basement in situ on the southern side, would be surprising.

But to validate our hypotheses we still have to wait until the earth has opened its every secret to us. In the meantime, we note that the gens PETICIA is well known in the X Regio Venezia et Histria through various inscriptions found in different places, providing good evidence of the spread of the family in the area.

Traces of fire, damage done to the floors by ruined material in the fall from above, document the little drama the building experienced perhaps as early as imperial times with the descent of barbarian prizes or opposing legions in the imperial struggles of the 3rd century.

The looting or flight of the inhabitants under the nightmare of danger meant that the best furnishings and what was salvageable were carried far away. This is perhaps why the excavation did not return anything that could tell us more about the men who animated with their existence the short stretch of space and time between the cobblestone and brick walls.

Valnea Scrinari

Valnea Scrinari è stata un’ archeologa triestina laureatasi dapprima a Trieste nel 1945 con il professor Mario Mirabella Roberti, di cui fu poi assistente, e poi a Roma, in Lettere classiche. Già Sovrintendente delle Venezie, si dedicò al Museo archeologico di Aquileia per passare successivamente alla Direzione della sovrintendenza alle antichità di Roma e poi di Ostia.

The villa in Ronchi of the Legionaries

Only the southeastern limit is known of this Roman-era rustic villa, which has been excavated only partially (covering an area of about 600 sq. m.), as the western part lies within the airport area. The archaeological site was identified in 1987 as a result of aqueduct work and was investigated on several occasions until 2007.

The villa, built around the middle of the 1st century BC, had three main construction phases and was finally destroyed by fire in the 3rd century AD.

The abandoned structures were later covered by the overflow of a watercourse (perhaps a branch of the Isonzo) that then flowed a short distance away. The U-shaped plan of the building was characterized by a series of rooms arranged,at different heights, around a central courtyard: the pars urbana, intended for the residence of the dominus (the owner), was located at a higher elevation. Reception rooms,characterized by floors with polychrome mosaics or black/white geometric patterns, faced outward on a columned portico facing the countryside or perhaps a garden.

Also in this area of the villa, a small room was equipped with a heating system with a suspensurae, brick columns that raised the floor allowing the passage of hot air coming from a nearby boiler.

The pars rustica, where the main production and processing activities of agricultural products took place was located across the courtyard. Here the rooms were smaller in size: some of them were paved with terracotta bricks.

The Gorgat mansion

In the area of the Gorgat, south of San Canzian d'Isonzo, work carried out in 1928 by the Brancolo Canal Reclamation Consortium brought to light, on the left bank, wall structures and a valuable mosaic floor with black and white tesserae and a meander frame; these remains probably refer to the residential part of a rustic villa.

Research conducted in the area in 1993 and 2006 allowed the collection of additional data, particularly on the dating of the complex, which can be attributed to a period ranging from the 1st to the 3rd century AD.

The extent of the villa is not known, but the discovery on the surface, after plowing, of a large amount of archaeological material-mostly building material-even on the other bank of the Brancolo canal suggests that the villa was large in size and extended further southward.