Villa at the ENEL plant

Nel 1965 la Soprintendenza alle Antichità delle Venezie indagò quel che rimaneva della villa, già individuata tra la fine dell’Ottocento e i primi del Novecento da Alberto Puschi e distrutta, nel corso della prima metà del Novecento, dalla costruzione della statale 14 e successivamente da quella della centrale ENEL.

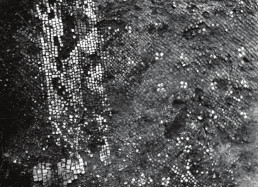

The investigation brought to light mosaic walls and floors. Of this villa, unfortunately, only photographic evidence remains: one of these relates to a room paved with a black mosaic with white crosses that finds comparisons with similar decorations attested in some Roman villas in the area dated to the second half of the first century BC.

Villa of the Point

The large complex, located on the island that formerly faced the mouth of the Timavo River, was investigated in the early 1970s.

It featured about 30 rooms arranged around a central courtyard.

To the north and northeast, in the residential wing, some rooms had floors decorated with black-and-white geometric mosaics; to the west was probably located the rustic part of the villa where production activities took place. The discovery of an olive press and stone elements traceable to a press seems to confirm this attribution.

A series of compartments, moreover, has been hypothetically interpreted as a thermal area. A mosaic with a central panel depicting two black dolphins facing a trident was found here.

These rooms opened onto a courtyard overlooking the lagoon; a boat was exceptionally found nearby. It, due to the construction technique employed ("mortise and tenon") was intended for use on the open sea.

Of the boat, datable like the residential building between the second half of the 1st century B.C. and the 2nd century A.D., the bottom was preserved, almost in its entirety (11 x 3.8 meters).

It is possible that it was used for the commercial distribution of the villa's products (oil, wine, fish sauces?). A number of everyday objects that were used on board were found inside the hull: ceramic vessels, a wicker basket and a wooden vessel containing grapes.

The wreck is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Aquileia.

Villa dei Tavoloni

Even of this villa, which was investigated several times between the 1950s and 1970s, nothing remains visible today.

From the excavation reports and photographic documentation it is assumed that the rustic part was characterized by a series of rooms arranged around a courtyard paved in cocciopesto and decorated with fragments of river pebbles.

Other rooms had wrought and terracotta tile floors arranged in a herringbone pattern (opus spicatum). Based on the archaeological materials found, it is possible to establish that the villa was inhabited from the second half of the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD.

Other structures of unclear interpretation brought to light in the surrounding area in the early twentieth century (perhaps a cistern, an enclosure wall, and a small pier) are probably to be related to the Tavoloni villa.

The villa of Casale Rondon

In the territory of San Canzian d'Isonzo, about two kilometers south of today's settlement, where the medieval mill of Rondon stood, fragments of a richly decorated polychrome mosaic floor, referable to the first half of the 3rd century A.D.The mosaic is documented only by photographs taken at the time of its discovery and was covered soon after by buildings of agricultural use.

It featured depictions of busts of athletes alternating with captions in Greek, enclosed in circular fields bordered by two-headed braids.

One section of the floor was decorated with a marine scene, very lacunar, of which only part of a cupid and a sea monster were preserved.

Although there is a lack of data on the structures and their extent, scholars believe that these mosaics were part of a large residential complex of the highest level equipped with baths, since the association of figures of athletes and marine scenes finds comparison with typical decorations in Roman-era bathhouse environments.

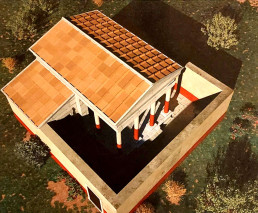

The Roman villa of Staranzano

Known as the "villa della liberta Peticia," the villa at Staranzano was one of the residences with a residential and productive character in the territory that in ancient times was administered by Aquileia.It was located along the Roman road that led from Aquileia to Tergeste (Trieste) and in the vicinity of a waterway, perhaps a branch of the Isonzo River that has disappeared today.

Like the other "ville rustiches" of the Roman period, the villa gravitated to a landed estate (fundus) where various economic activities were carried out, from which the owner and his family drew sustenance and products to market. These complexes consisted of a residential part (pars urbana) and a purely productive part (pars rustica).

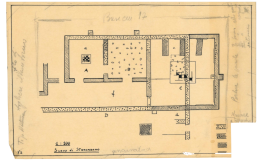

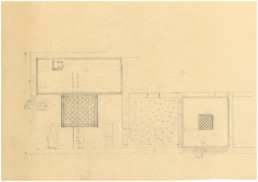

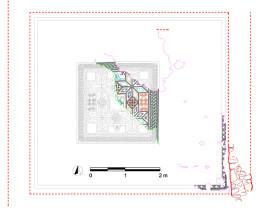

The Staranzano villa was discovered by chance in 1955 on land owned by the parish church during work to modernize the sewage system. Archaeological excavations, conducted by Valnea Scrinari on behalf of the Venetian Superintendence of Antiquities, brought to light only the southeastern corner of the building, at a depth of about 80 cm from ground level and covering an area of about 130 sq. m.

From these early investigations remain the notes and sketches that Giovanni Battista Brusin, archaeologist and director of the Archaeological Museum of Aquileia from 1922 to 1952, recorded in his diaries. Other limited surveys and restoration and conservation work on the structures were carried out in 2002 and 2008 by the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici del Friuli Venezia Giulia.

The size of the villa is currently unknown. Recent geoarchaeological investigations carried out in 2022 as part of the "E-VILLAE" project promoted by the Municipality of Staranzano have made it possible to identify, to the southeast of the already excavated complex, traces of at least two rooms probably pertaining to the villa but not physically connected to the residential part.

The first building of the complex is dated to the second half of the 1st century BC. Based on archaeological data, we know that between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD changes were made to the building during at least two phases of renovation.

The villa was inhabited until the beginning of the third century AD. Renovations involved not only changes in the size of the rooms, but also the use of different building materials in the masonry: the earliest phase saw the use of river pebbles, while in more recent ones brick fragments and tiles were also used. The latter were often stamped with trademarks referring to well-known local manufacturers.

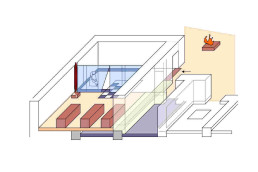

The 1955 excavation brought to light three identical rooms, paved in opus caementicium (beaten mortar incorporating flakes of stones of different colors), placed side by side and facing a long and narrow room, perhaps a courtyard, referable to the first building phase.

During the first renovation, the room to the southeast (A) was considerably enlarged: one part was paved in terracotta cubes and the other in black and white tessellation; a black and white checkerboard mosaic (emblem) was inserted in the center of the room. This room was possibly used as a triclinium (dining room), with the triclinar beds probably arranged on the terracotta-paved area.

The northernmost room (C), now covered by a canopy, was also repaved with a white-tile mosaic framed by a black-tile band.

A black-and-white checkerboard pattern was inserted in the center of the floor, also bordered by a black frame.

The last renovation,characterized by a sloppy construction technique,made significant changes to the great hall (A).

Part of it was subdivided into four small rooms or cells by walls.

The discovery of a squared stone block with a central hole (D),juxtaposed to the perimeter wall of the housein correspondence with an external buttress, leads to the hypothesis that a post was inserted there to support a movable partition (e.g., a curtain): this would have allowed the room to be further divided, creating a sort of antechamber and preventing the view of the cells. Such elements suggest the transformation of this part of the villa into a sacellum, that is, a place intended for a domestic cult.

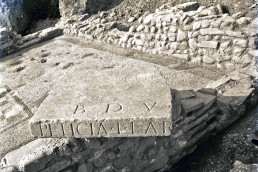

The room was entered from the courtyard through a door documented by the finding of a stone threshold (E) with hinge holes. This transformation into a sacellum is corroborated by the finding, in this room, of a large stone slab (dimensions preserved 57 x 57 cm), possibly a mensa, a kind of table for ritual offerings.

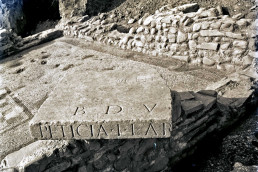

It bears engraved the inscription B(onae) D(eae) V(otum) / PETICIA L(uci) L(iberta) AR[-] testifying to the dissolution of a vow made by Peticia, a freedwoman (freed slave) of the Peticii family, to the Bona Dea.

The inscription is dated between the end of the first century B.C. and the first half of the first century A.D. and thus testifies that the cult to the Bona Dea was practiced in the Staranzano villa already during its first phase of establishment.

A large quadrangular platform was also found in the inner courtyard of the complex, paved with terracotta cubes, whose function or possible relationship to the sacellum is unknown.

The cult of Bona Deaera particularly widespread in the territory of Aquileia and was connoted as a mystery cult, practiced only by women, whose characters could not be known to men. Celebrations were held in public form in temples but also in private form inside homes; free women and enfranchised slaves participated.

The presence of the small cells in room A of the villa harkens back to sacred buildings dedicated aquesta deity salutifera, for example the temple of Bona Dea Subsaxana on the Aventine Hill in Rome or the one identified in the center of Trieste in 1910, where the cells were perhaps intended for the performance of divination activities or healing rites.

Understanding the architectural features of the Staranzano villa and reconstructing its phases of occupation are particularly problematic because of the paucity of everyday materials recovered during archaeological investigations, such as pottery and amphorae. Only stamped tiles and a few metal objects, such as a bronze net needle, are mentioned in the 1955 excavation diaries.

Randaccio's Villa

The villa, of which 40 rooms covering an area of about 1,300 square meters have been unearthed, is located within the park of the Trieste Aqueduct "Giovanni Randaccio" near the resurgences of the Timavo River.

The building's rooms were arranged on three levels partly exploiting the rocky slope of a karst high ground.

The excavation, made problematic by the constant rising of groundwater, allowed for the investigation of a sector of the residential part of the villa. It was founded by the middle of the first century B.C.E. and was modified four times: in the Augustan period (27 B.C.-14 A.D.) the floors of the rooms were covered with black and white mosaics with cross, star, lozenge, and crenellated wall motifs; in the third phase, between the end of the first and the beginning of the second century A.D., the villa was expanded and some rooms were equipped with floor and wall heating by means of cavities and pipes for the passage of air heated by a boiler.

In the last phase, between the 3rd and early 4th centuries AD, the building, already partly abandoned, was remodeled with the implantation of production-type structures (some tanks and a hearth).

The complex, because of its size and proximity to the road from Aquileia to Tergeste, has been interpreted as a mansio, i.e., as one of the rest stations for resting travelers and horses, located along the evenly spaced streets.

Scholars identify this mansio in the illustrated road station at the Fons Timavi at Tabula Peutingeriana, medieval copy of a painted itinerary from the Roman period (probably from the second half of the 4th century AD).

Villa of Via dei Bagni Nuova

As part of urbanization works conducted in 2015 in Monfalcone, the remains of three rooms pertaining to a villa were discovered. One of them, which can be interpreted as a reception room, was paved with a valuable white-tiled mosaic carpet bordered by a black-and-white-tiled frame. In the center, the floor was adorned with a polychrome panel with geometric designs.

Within this frame, in a central position, stands a depiction of a chalice from which red and black racemes emerge.

The mosaic dates to the second half of the second century AD, but the room in which it is found and perhaps the entire building probably date to the second half of the previous century.

The discovery of marble slabs and tubules from heating suggest the existence of thermal or otherwise heated environments in one of the life stages of the complex.

Archaeological data allow us to place the abandonment of the villa in a period between the late 3rd century and early 4th century AD.

Villa on Mandrie Street

The building, investigated between 1990 and 1997, consisted of a multi-level main body joined by two lateral structures that opened onto a central courtyard, so that the floor plan took on a U-shape.

Excavations have revealed two phases of building and use of the villa over a period of time from the second half of the first century B.C. to the third century A.D. The dwelling, which on the basis of the building materials used (mosaic tiles, marble slabs, painted plaster, heating pipes, and fragments of glass window panes), must certainly have been a prestigious residence, characterized by residential, productive, and thermal environments, and was probably connected to a small dock.

This also allowed goods and merchandise to arrive by sea.

Archaeological and archaeozoological records indicate that among the economic activities carried out in the rustic part of the villa were those of sheep breeding and wool production.

Columbus Street Villa

Archaeological excavations conducted between 1992 and 1996 brought to light the remains of structures referable to a villa whose rooms developed between the first karst reliefs to the north and the sea. The residential part was characterized by rooms whose floors were decorated with refined mosaics with geometric motifs in black and white; the rooms, located around a courtyard, were probably arranged on terraces at different heights so as to articulate, even scenographically, the building.

In contrast, to the south was an area dedicated to productive activities, a very large basin measuring 20 x 15 meters, which, based on its structural features, has been interpreted as a private dock: there were possibly fish or shellfish breeding facilities here.

A corridor, believed to be a loggia due to the presence of limestone column bases, connected the residential part with the dock.

The villa was built in the second half of the 1st century B.C. and underwent renovation around the middle of the 1st century A.D., at which time the dock was built. The building complex was then permanently abandoned during the 2nd century AD.

Villa at the Marcelliana church

The structures, identified in the late 19th century by Enrico Maionica, are said to refer to several rooms facing a porticoed courtyard. The floor of one of them was decorated by a mosaic with a complex black-and-white geometric pattern datable to the 2nd century AD.