Conclusions

Geophysical prospecting carried out in the area of the Liberta Peticia villa enabled the collection of a number of archaeologically and topographically interesting data.

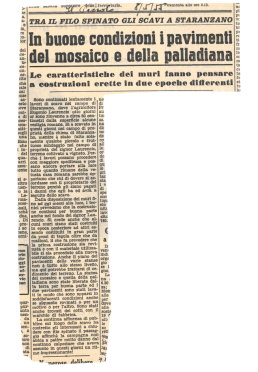

Net of the impossibility of covering a homogeneous unobstructed area, it was possible to point out the presence of a number of anomalies, the most interesting of which are those related to probable structures located to the south of the main building and most likely forming part of outbuildings related to it.

The depth of the anomalies referable to masonry structures is certainly compatible with those of the villa, suggesting that they belong to the same chronological scope.

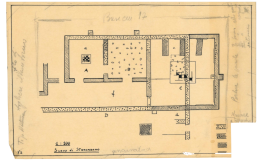

A second important fact to take into account is the lack of anomalies referable to masonry structures in the area immediately south of the villa and thus in physical connection with it. This fact seems to prove that the rooms identified during excavation represent the southeastern limit of the building and that the remaining rooms of the villa are to be sought toward the north and in the field west of it, as assumed in the image below.

Results

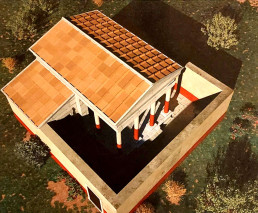

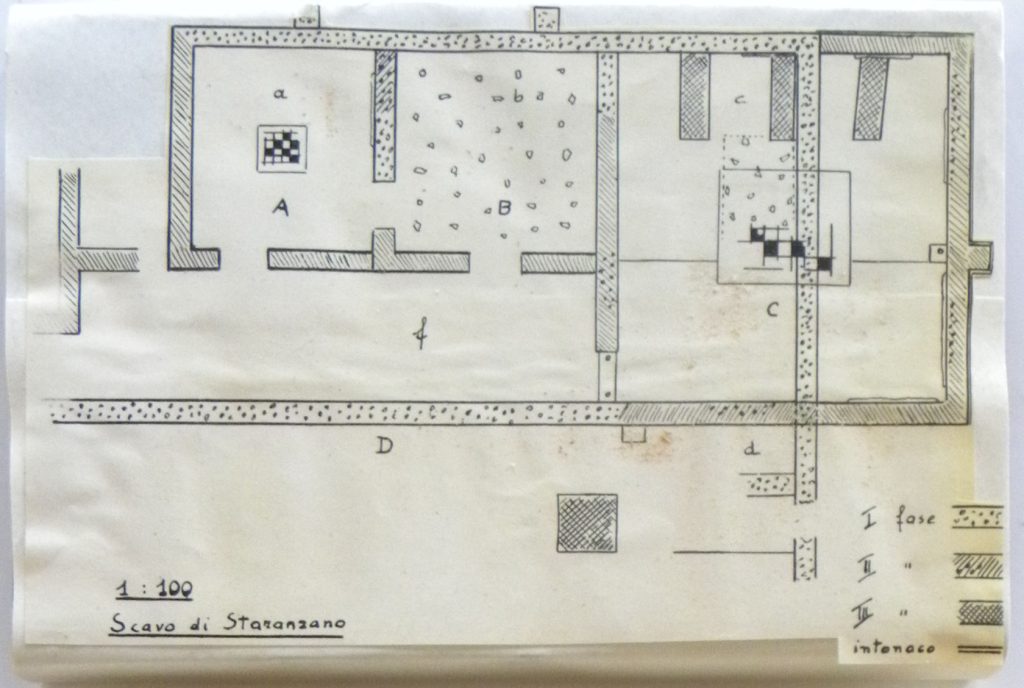

The structures related to the villa identified during the excavation phase are represented by at least three rooms aligned on a southeast/northwest axis open to a probable uncovered area located to the west of them.

The structure shows at least three phases of renovation, in the last of which, the largest room located south and st of the structure and recognized as a triclinium, was subdivided into smaller rooms.

The characteristics of the identified wall structures, the lack of openings along the east and south walls of the rooms and of traces of walls on the external face, seem to indicate that the portion of the villa discovered is the one related to the southeastern corner, and that it therefore developed towards the north and west, for an estimated extension d i 2500 square meters.

The archaeological data recovered as a result of the excavations would thus seem to validate the hypothesis that in the area south of the structures there may be no masonry structures belonging to the main body of the villa, a theory that does not, however, imply the lack of buildings or outbuildings pertaining to the villa but not physically connected to it.

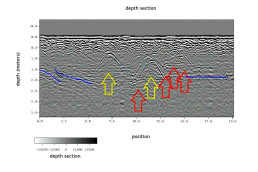

Georadar surveys have identified some interesting anomalies at an average depth estimated between 60 to 1 meter in depth, the same elevation at which the ridges of the identified structures stand.

The data were interpreted in order to identify any anomalies attributable to buried structures of archaeological interest.

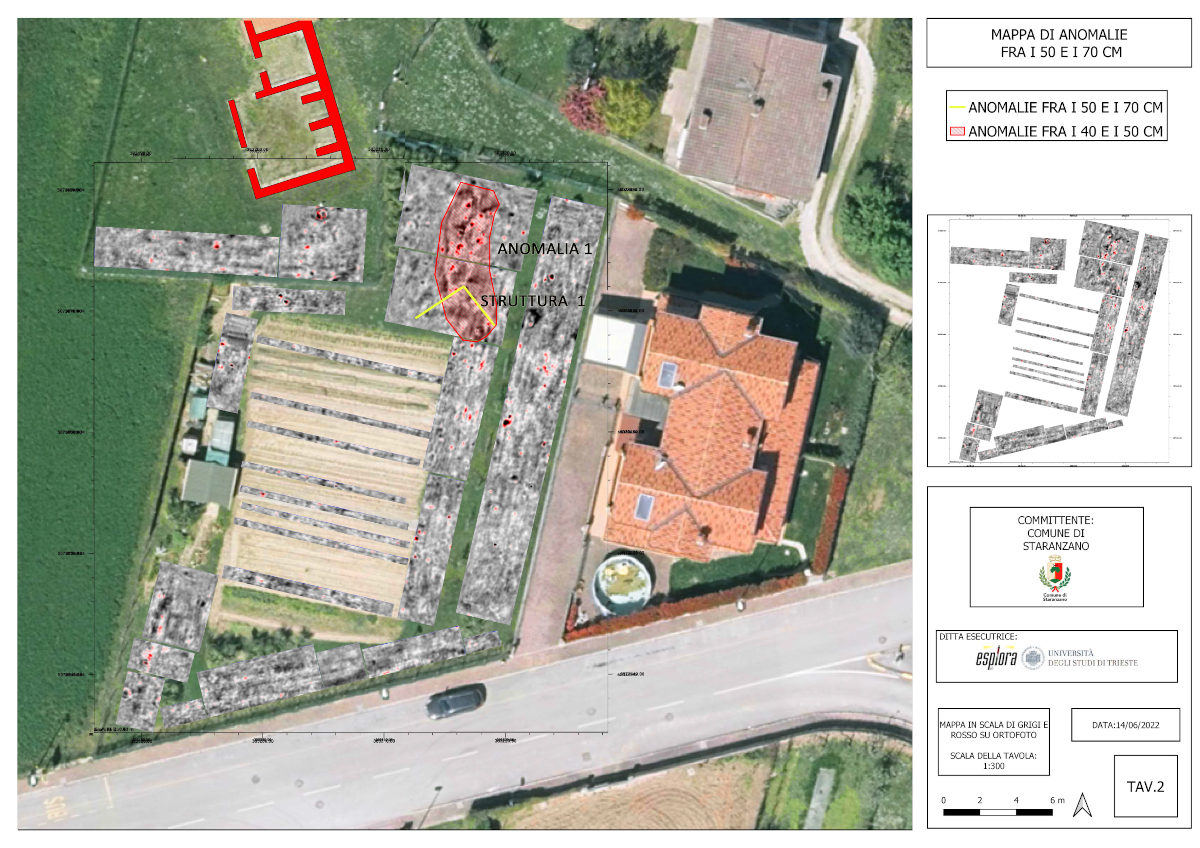

Data processing identified three distinct groups of anomalies located at different depths from 40-50 cm above ground level, all in the eastern range of the field.

The anomalies were classified according to their type, stratigraphic position, and geometry.

It should be pointed out that an error in depth of +/-0.15-0.20m should be considered for depth and -/+0.10-0.15m for width of anomalies, due to instrument resolution, interference and possible systematic errors.

Tables

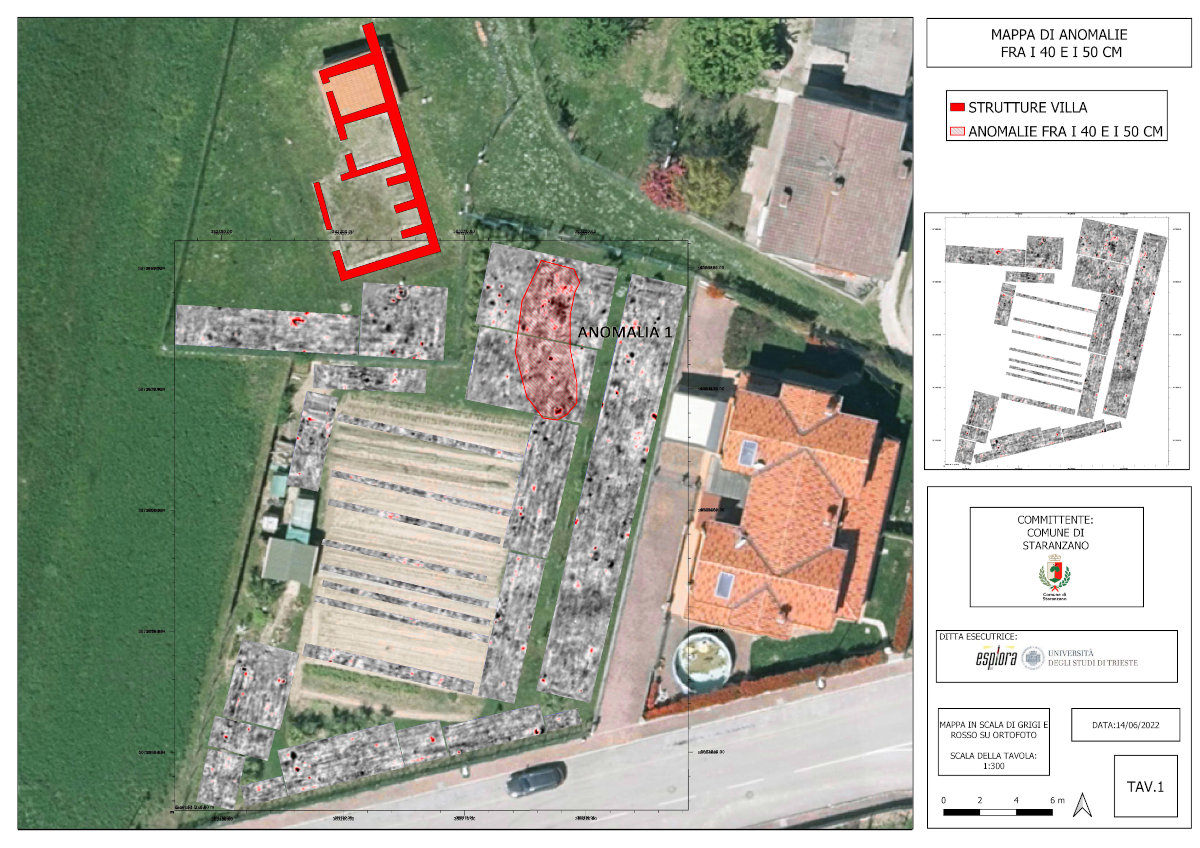

Table 1 - Depth between 40 and 50 cm: In the northeastern part of the field, immediately southeast of the villa structures, an irregularly shaped anomaly appears at a depth of about 50 cm, running from north to south covering an area of about 60 square meters (see below image 'longitudinal and cross sections of Anomaly 1').

From its shape and development in depth, the anomaly is funnel-shaped and could be associated with a pit filled with inconsistent material, probably a post-depositional intervention that also affected the underlying archaeological levels.

It is conceivable that it can be explained as an intervention of destruction or spoliation of underlying structures.

The hypothesis could be supported by the presence in the same area, from 50 cm depth, of traces of linear anomalies that, descending in the stratigraphy, assume a more linear geometry, revealing themselves as probable wall structures related to a building located southeast of the villa structure.

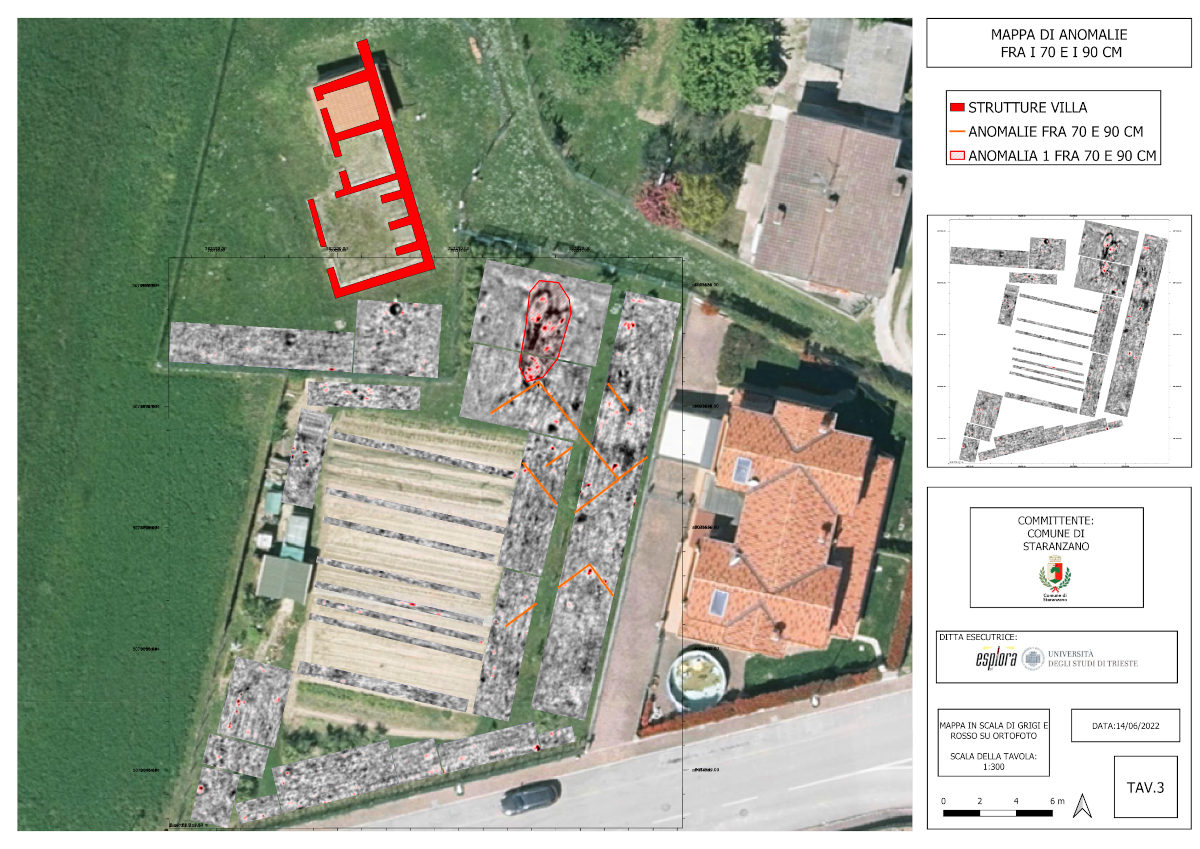

Table 2 and Table 3 - Depth between 70 and 90 cm: At this depth the wall structures identified in the higher levels take on a more precise physiognomy, while the trench reaches maximum visibility before disappearing around the depth of 1.20 m. From 70 cm other linear and isoriented anomalies are added to those already highlighted in the higher levels, probably as a matter of preservation of the elevations.

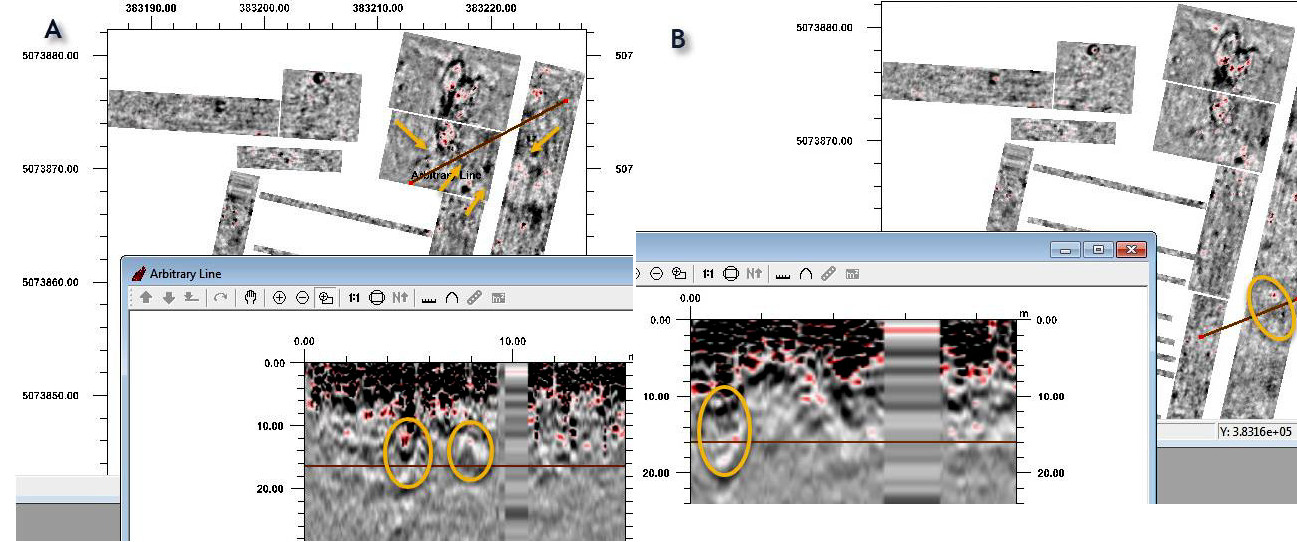

In more detail, the first building (see below image 'A evidence from Structure 1) seems to be characterized by two longer walls with a northwest/southeast orientation (the east one is visible in its entirety), at the ends of which are two smaller arms perpendicular to these: the space created by these walls seems to be further divided into two rooms by an intermediate wall septum. At the level of the southeastern head of the east wall of the building we seem to see the trace of an additional structure running eastward and extending the southern limit of the building on this side. East of the longer wall is the trace of a further wall alignment, parallel to it and probably pertaining to the eastern limit of a third room. Of the second building (see image 'B evidence of Structure 2' below), located to the south of this one, a long wall is identifiable that runs parallel to the south side of the first, and a second structure that creates a 90-degree angle to the southeast, starting from the east head of this one.

The sign is less legible than that for the first building, probably because of the level of preservation.

At this depth it is therefore possible to reconstruct the presence of at least two buildings, oriented toward each otherand not physically connected to the main body of the villa.

The orientation of the identified buildings also does not reflect that drawn by the walls exposed in the excavation, although this element does not collide with a direct relationship between the structures.

Depths between 90 and 120 cm: the signals related to the first structure are readable up to a depth of 1.10 m, after which it becomes more difficult to read its geometry. As for the anomaly related to the ditch, this is clearly identified at least up to a depth of 1.20 m, and then gradually disappears.

Data processing

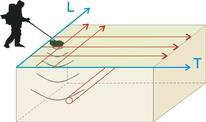

3D GPR data are processed in order to recreate a volume in x,y spatial coordinates and z (depth) in temporal coordinates or converted to depth.

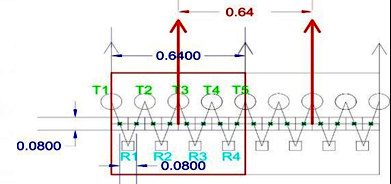

Each recording involves the acquisition of 8 profiles simultaneously, so that the information obtained is that of a 64cm band.

The raw data (raw data) to be processed is then a number of "bands" equal to the number of profiles run.

The raw data undergoes a pre-processing step to improve the signal-to-noise ratio; the processing steps that are applied to the data set is as follows:

- Amplitude correction

- Antenna Ringdown removal

- Bandpass filtering

Next comes the interpolation phase, in order to integrate information between records. This is done by selecting a box, within which the interpolation algorithms will take place.

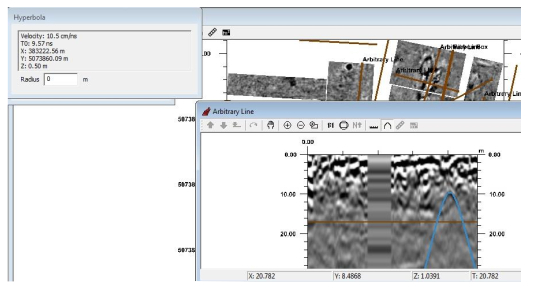

Depth conversion is done after estimating the velocity of the electromagnetic wave in the medium according to the diffraction hyperbole analysis procedure, and the subsequent migration procedure. The velocity measurement is made on the basis of the analysis of diffraction hyperbolas, the aperture of which depends on the dielectric constant of the medium and thus the velocity of the electromagnetic wave.

At this site, however, no hyperbola was found on which to estimate the propagation velocity. A velocity of 10.5 cm/ns was estimated under these conditions, based on analysis of diffraction hyperbolas.

The migration procedure results in a GPR image for which the anomalies are higher resolution and in which the diffraction hyperbolas are focused into point units.

After the migrated volume is obtained, the software allows the entire area covered by the GPR to be analyzed in plan as a function of depth and the different maps (slices) to be analyzed and then proceeded with interpretation.

To recap, the processing sequence applied to the data volume includes:

Import raw data

• DC removal

• Drift removal

Pre-processing

• Amplitude correction

• Antenna Ringdown removal

• Bandpass filtering

Processing

• Interpolation

• Migration

Post processing

• Amplitude analysis

• Slice interpretation

Data acquisition

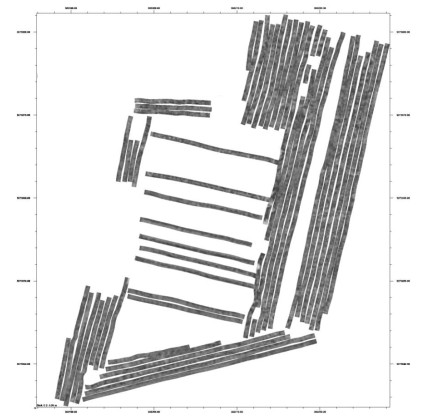

3D Georadar data acquisition was performed in the vacant area located south of the archaeological area on May 24, 2022.

A GNSS ( Global Navigation Satellite System) receiver was used for GPS positioning, connected via GPRS (General Packet Radio Service) to the NRTK (Network Realtime Kinematic Satellite) differential real-time corrections network. The GNSS receiver was installed directly on the Georadar apparatus.

Georeferencing was performed in the WGS84 coordinate system UTM33N zone thanks to the in situ topographic survey of some evidences in the area.

The purpose of the survey was to identify the presence of additional masonry structures belonging to the villa in the only area for now that can be traversed with Georadar.

In fact, the archaeological area is surrounded by land belonging to private individuals, some of which is built-up and difficult to traverse with this instrumentation.

The same area covered by prospecting had a number of problems, related to the presence of areas planted with vegetable gardens, and a part occupied by some service sheds.

As a result, the particular lay of the land did not allow for complete coverage of the area, covering an area of about 730 square meters.

Parametri utilizzati per il rilevo Georadar

- Frequency Shielded antennas: 400MHz

- Total antenna offset: 0.64m

- Number of channels: 8

- Communication: Ethernet

- Positioning: GPS-RTK and odometer

- Power supply: 12V 45Ah battery

- Spatial sampling interval: 0.08m

- Number of samples per track: 436

- Time window length: 97.26ns

- Vertical stack: 4

Georadar GPR survey: physical principles

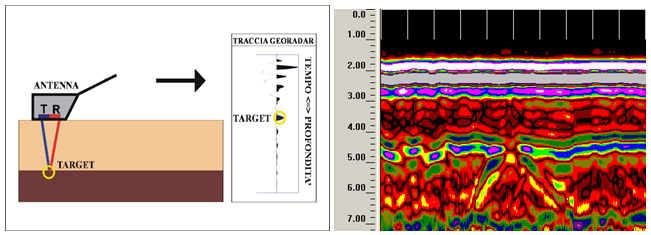

To finalize the 3D geophysical investigations, we made use of ground penetrating radar (GPR) georadar, which allows us to investigate both the subsurface and structures and noninvasively reveal the possible presence and location of buried objects, metal objects, and anomalies in masonry structures using the phenomenon of electromagnetic wave reflection.

The method of analysis is based on the principle of propagation of electromagnetic pulses in materials and their reflection at those discontinuity surfaces attributable to changes in permectivity of the materials investigated.

Data acquisition is accomplished by sliding a pair of antennas (one transmitter and one receiver) maintained at a constant distance over the surface to be investigated.

In the central unit of the apparatus, signals are generated at regular intervals that serve to stress the electronic circuits of the transmitting antenna.

Electromagnetic pulses are radiated from this, which, propagating through materials, are reflected at the interfaces between materials with different dielectric characteristics.

Reflected events are picked up by the receiving element and sent into the central unit for further processing.

The equipment allows real-time display of the recorded radargram on a color display for preliminary quality control, and simultaneously stores the data on associated notebook for later processing with dedicated software.

Subsequent digital processing of the data makes it possible to improve the interpretability of the acquired data through filtering operations, normalization, amplification, etc. in order to make the presence of any anomalies more obvious.

On the horizontal axis of the radargrams are displayed the metric progressions of the recorded line, while on the vertical axis are the double path times (outward and return) of the reflected paths.

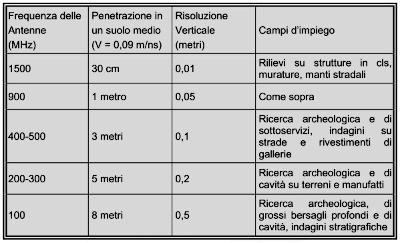

The horizontal resolution of the signals is inversely proportional to the speed at which the antenna is moved; the vertical resolution is directly proportional to the center frequency of the emitted pulses.

The intensity of reflected events is stronger the greater the contrast between dielectric variations.

The depth of investigation cannot be established a priori of the survey but depends on the absorption of electro magnetic energy by the materials in which it propagates. The depth depends on the nature of the media traversed, the physical state of the constituent elements, and environmental and/or local factors: temperature, humidity, presence of cavities, etc.

Moreover, the prospecting target and penetration depth are constrained by the wavelength of the pulses: in fact, if a buried structure is very small in size, it is detected only with signals of very short duration whose high attenuation at the energy level, however, limits its penetration.

In summary, antennas with high frequencies allow good resolution down to modest depths; antennas with low frequencies offer relatively less detail, but allow a greater extent of measurement from the surface topography.

The presence of water or moisture in the materials under examined, results in an increase in the relative dielectric constant and thus a decrease in the speed of electromagnetic pulses. Knowledge of the relative dielectric constant is useful in determining the type of material being investigated and its degree of moisture.

The definition of such anomalies is provided at the data interpretation stage, based on the type (e.g., shape of the object that caused the reflection) and planimetric continuity of identical or, at any rate, similar events.

It is important to remember that the measurement procedures used for the geophysical survey of Villa Peticia are based on indirect exploration techniques that have a number of inherent limitations regarding the propagation of the electromagnetic wave. This wave depends on the dielectric constant of the materials: in clay materials with high dielectric constant or in the presence of water, the attenuation of the signal is high with the risk of not detecting any discontinuities/objects present.

The geophysical survey cannot all way never be considered a complete substitute for direct exploration.

The Georadar system used

A 3D georadar system, equipped with 9 shielded antennas at 400MHz, was used in the present investigation for exploration depths within 3m.

The system encloses within it 5 transmitting and 4 receiving antennas of the same frequency, and the combination of transmitting and receiving causes 8 parallel profiles to be obtained simultaneously at each pass.

The 8 profiles are spaced by a fixed offset of 8cm. Together they occupy a 64cm band. The positioning system involves the use of an odometer and where possible interfacing with GPS or total station.

This very complex system was developed to identify archaeological finds quickly and with very high resolution.

The system facilitates the interpretation of the signal by highlighting continuous structures, and avoids making errors in interpolations of 2-dimensional profiles.

Acquisition in the 3 directions of space makes acquisition independent of the often unknown orientation of the target.

The 3D system is connected to a laptop from which acquisition parameters can be managed and the acquisition of each swipe can be viewed in real time.

The technological limit ical limitation of the 2D and 3D georadar methodology, in each case is the depth of the water table, since it completely absorbs the electromagnetic signal.

geophysical surveys 3d for the identification of buried structures

il video dedicato alle fasi di ricerca e studio

In May 2022, some geophysical investigations using 3D georadar were carried out at the Roman villa of Liberta Peticia in Staranzano, aimed at verifying the presence of eventual ali buried structures in the vicinity of the archaeological site.

Queste prospezioni geofisiche effettuate nell’area della villa hanno consentito di raccogliere una serie di dati interessanti dal punto di vista archeologico e topografico, sebbene al netto dell’impossibilità di coprire una superficie omogenea priva di ostacoli, per via della presenza di campi coltivati e di capanni ad uso agricolo presenti sul sedime d’indagine.

Le varie fasi dell’indagine sotto riportata, congiuntamente alla spiegazione dei principi fisici afferenti a questa, restituiscono un piccolo, affascinante viaggio nell’applicazione delle più moderne metodologie scientifiche alla scoperta di quell’antico che ancor’oggi cela i suoi segreti nella campagna locale.

Le presenti ricerche archeologiche non invasive sono autorizzate dal Ministero della Cultura – Direzione generale Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio / Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio del Friuli Venezia Giulia con protocollo n° 3619 del 25/02/2022.

conservation intervention on the mosaic floor

il video dedicato all'intervento conservativo

STATE OF PRESERVATION

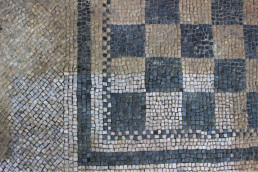

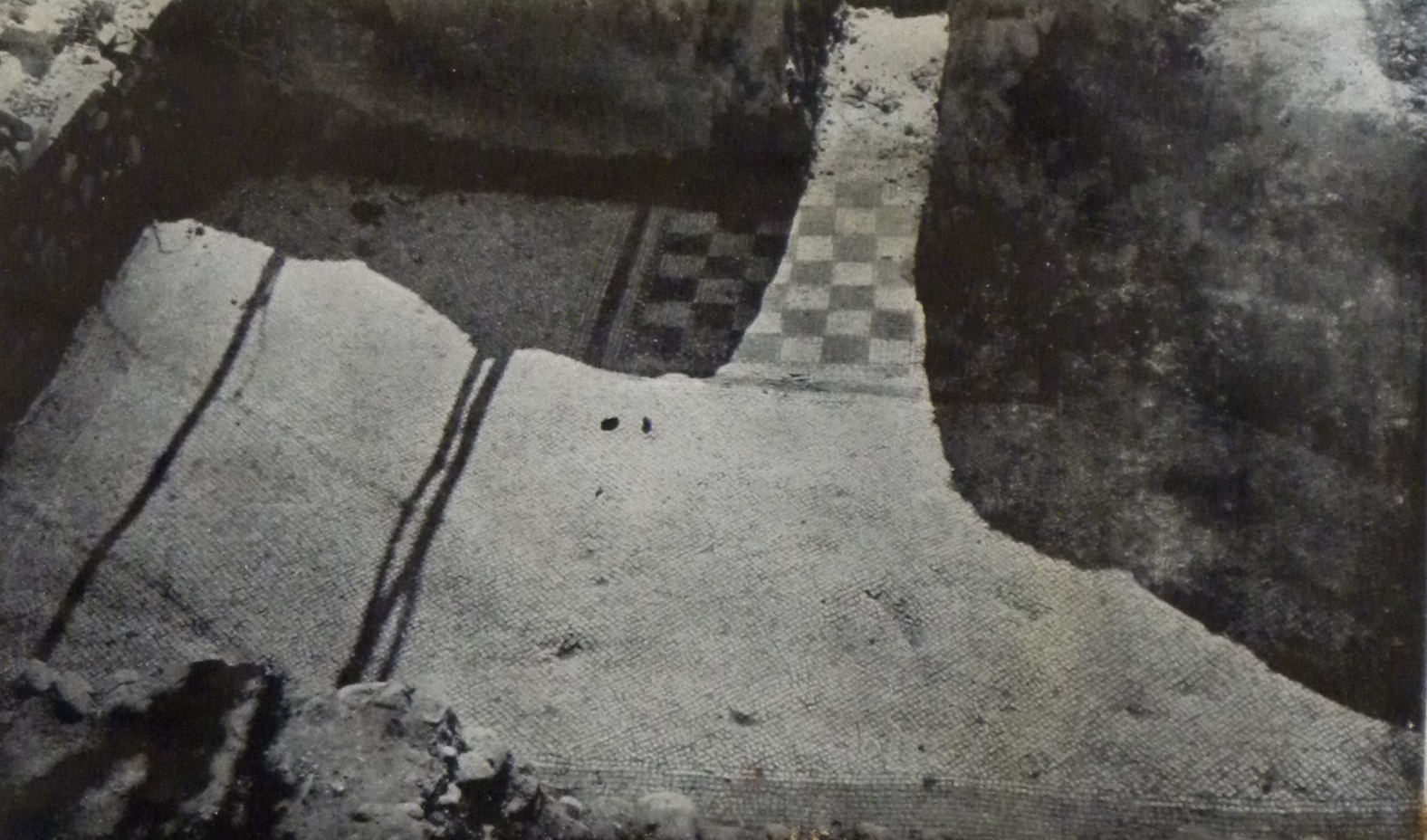

The E-Villae project included conservation work on the mosaic of the Roman villa in Staranzano, intervening on the state of conservation of the mosaic, which, seven years after the last restoration work, was still in fair condition.

On initial analysis, the grouting of the perimeter margin was locally fragmented resulting in the detachment of the last rows of tiles, and the entire room was covered with dusty environmental deposits, plant and animal residues that rendered the central checkerboard and the chromatic value of the constituent materials illegible.

The mosaic surface was found to be populated with green algae whose color was intensified by bringing in moisture, higher type seedlings, and moss, especially along the interstitial mats.

The physical barricades at the two entrances proved insufficient to protect the pavement from biological attack, making it possible for numerous higher type plants and mosses to be present at the thresholds.

THE RESTORATION WORK

The first operation carried out by the restorers was disinfection by spray application of environmentally friendly biocide.

The product was spread on all mosaic and masonry surfaces and left to act for a few days. At the same time, the upper plants were uprooted from the terracotta of the entrances with the utmost caution to avert the risk of disconnection.

Biocide treatment was repeated at the end of the intervention before final protection.

Preliminary dusting was an extremely important operation in order to understand the degree of adhesion and cohesion of the tessellation and to identify unraveled tiles. For this reason, it was patiently performed manually using soft brushes

At the same time, mechanical removal of moss along the interstices of the tiles was carried out using a scalpel.

The dusting revealed a very blurred surface, the reading of which was still very laborious. To deepen the removal of inconsistent deposits the entire surface was washed with vaporjets, nylon brushes and cellulose sponges, taking care to collect water stagnation to allow for rapid drying.

The dusting revealed a very blurred surface, the reading of which was still very laborious. To deepen the removal of inconsistent deposits the entire surface was washed with vaporjets, nylon brushes and cellulose sponges, taking care to collect water stagnation to allow for rapid drying.

The perimeter saves were supplemented in the ruined portions with lime and sand-based mortar added with powdered pigments.

Tiles that were movable but sufficiently anchored to the bedding mortar were fixed with injections of acrylic resin in an aqueous suspension, while those that were completely detached were relocated with bedding mortar.

However, some tiles were lost, so they were replaced using stone tiles of a similar lithotype to the original one.

Although large amounts of topsoil were removed by sponge washing and steaming, however, the initial aesthetic result was not entirely satisfactory.

Therefore, planning to carry out the consolidation, in agreement with the Construction Management, it was decided to deepen the cleaning of the tessellated tiles with the use of the micro-sandblaster, so as to dry remove even the concreted earthy deposits and ensure the proper penetration of the consolidating product on the surfaces of the tiles and in the interstitial mortars.

As expected, the operation brought out the chromatic value of the materials and enabled the removal of mosses from the interstitial spaces to be perfected.

Once the cleaning was finished, grouting was done in places where they were damaged and where higher plants had developed.

The joints between the bricks in the thresholds were also filled with lime mortar and pigmented sand in order to slow down the resurgence of plant growth.

A consolidating and water-repellent product based on ethyl silicate combined with siloxanes was spread on the perfectly cleaned and dusted surface with an electric vacuum cleaner and brush.

The latter treatment thus allows for better resistance of the treated surface, predisposing it favorably to periodic, venturous conservation work.

the 2003 recovery and restoration project

The discovery of the villa occurred fortuitously 1955.

It was immediately followed by a campaign of excavations directed by the Veneto Archaeological Superintendency. Thanks to this work, the southeastern end of the villa was brought to light, which turned out to have been built in the second half of the first century B.C. near the consular road from Aquileia to Tergeste.

The current excavations, aimed at enhancing the site, have unearthed the two perimeter structures east and south of the villa, buttressed on the outside by quadrangular pillars. Inside, the space is divided into three rooms facing an uncovered, courtyard-like area, the floors of which are still in good condition.

The first phase of construction is characterized by the use of river pebbles as construction material. The floors are made of signino, that is, a wrought stone of limestone fragments and mortar, which is superiorly smoothed and decorated by the deliberately haphazard insertion of sections of pebbles and stones of various colors.

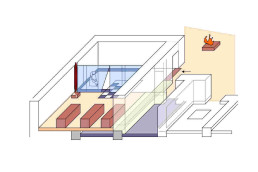

In a second phase of renovation of the villa, which we could date in the first half of the first century AD, the first room is enlarged through the construction of a new perimeter wall moved southward: the technique used is different, a fact that helps to distinguish between the various building phases, and it employs not only river pebbles but also fragments of brick tiles perhaps partly recovered from the demolition of elevations or roofs referable to the previous structures.

At this stage, over the shaving of the old perimeter and over the previous floor, another one in terracotta cubes is laid, which on the line of extension of the wall closing the adjacent rooms, gives way to a black-white mosaic with a central checkerboard decoration. It is precisely the central position of the decoration, which outlines a U-shaped arrangement in the cube floor, that has led to the room being identified with a triclinium, a dining room where the cubed paved area was "hidden" by the arrangement, in a "U" shape precisely, of triclinar beds, on which the Romans used to eat while lying down leaning on one elbow.

In this phase the old courtyard is also expanded and paved with cubes while the second room retains the previous signino; the last room investigated to the east, the third, is itself adorned with a black-and-white mosaic with another small central checkerboard.

The third phase, which is notable for a decidedly shoddy and hasty construction technique, makes some non-substantial changes to the facility.

Il primo vano è oggetto di una ristrutturazione che lo porta a cambiare di destinazione d’uso: la sala viene quadruplicata attraverso la costruzione di tre tramezzi (è probabile infatti che essi non raggiungessero l’altezza l’altezza totale della stanza, sino al soffitto) e l’ingresso si orna di una soglia in pietra che conserva l’incasso della porta.

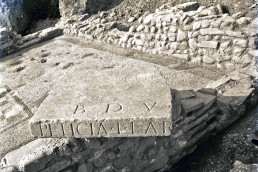

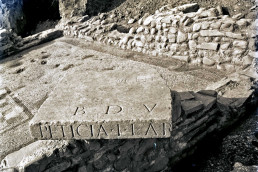

Molto probabilmente, l’accesso diretto alle quattro celle era impedito da un aulaeum, una tenda in stoffa leggera che correva lungo la fascia di passaggio tra il mosaico ed il pavimento a cubetti: un piccolo plinto in pietra fornito di incasso per un palo, rinvenuto in posizione originaria, addossato al muro perimetrale ed in corrispondenza della fascia di passaggio è forse da collegare al suo sostegno.Durante lo scavo del 1955, il rinvenimento in questa sala di una base con dedica alla Bona Dea by the freedwoman Peticia, has led to the recognition of a private sacellum there: however, the earliest dating of the epigraph -end of the 1st century B.C./early 1st century A.D.- proves that worship was already practiced in the villa from the beginning of its construction, a fact that does not prevent, however, that Bona Dea was worshipped there a century later.

Also probably to be connected to cult rituals is a quadrangular platform, glimpsed in the courtyard at the eastern end of the excavation, which hypothetically we could identify with an open-air hearth.

Risultati culturali e scientifici raggiunti.

With the conclusion in the construction site, a part of the Roman villa is usable to the entire citizenry.

With the conclusion at the construction site, a part of the Roman villa is usable for the entire citizenry. An educational panel describes the visible structures in a clear and simple way with the help also of photos and drawings. A panel placed on the road indicates the positioning of the villa.

The paucity from the funding did not allow the mosaic floors to be unearthed as well, so it is hoped that future interventions are directed toward this, to make the internal distribution of the Roman villa more understandable.

During archaeological excavation operations to unearth the structures identified in the 1950s, a number of soundings were carried out to also check the state of preservation of the villa's floors in order to budget for future interventions.

Contained in the documentation al produced by the archaeologists at the end of the excavation are confirmations to published reports from the 1950s verifying the importance of the rustic villa at Staranzano.

The structures were consolidated and protected with a sacrificial surface, made of pebbles for those of the first phase and of bricks for those of the second phase. The first phase structures were covered with a double course of stones, the first one slightly recessed from the outer edge to denote the new part of the original facing.

Quelle di prima fase sono state ricoperte da un corso di mattoni con la seguente metodologia: vista la non sufficienza di mattoni originali disponibili, questi sono stati utilizzati per proteggere i pavimenti esterni collocando verso il basso la ripiegatura a protezione del paramento sottostante. L’interno delle strutture è stato protetto con mattoni nuovi ma fatti a mano. Sono stati effettuati vari campioni di malta per raggiungere la coloritura e la composizione più simile a quella originale e più resistente nelle condizioni ambientali del luogo. I pavimenti sono stati protetti con geotessuto, sabbia e ghiaia. Il geotessuto è stato posizionato secondo pendenze calcolate atte convogliare l’acqua piovana in una zona posta a sudovest ed esterna al sedime della villa, ove è stato collocato un pozzo perdente. L’area risulta interamente recintata da una rete verde che garantisce la sicurezza al monumento ma permette a chiunque di vederlo ed è dotata di un impianto di illuminazione di sicurezza.

Arch. Fabiana Pieri

The Roman villa of Staranzano

Known as the "villa della liberta Peticia," the villa at Staranzano was one of the residences with a residential and productive character in the territory that in ancient times was administered by Aquileia.It was located along the Roman road that led from Aquileia to Tergeste (Trieste) and in the vicinity of a waterway, perhaps a branch of the Isonzo River that has disappeared today.

Like the other "ville rustiches" of the Roman period, the villa gravitated to a landed estate (fundus) where various economic activities were carried out, from which the owner and his family drew sustenance and products to market. These complexes consisted of a residential part (pars urbana) and a purely productive part (pars rustica).

The Staranzano villa was discovered by chance in 1955 on land owned by the parish church during work to modernize the sewage system. Archaeological excavations, conducted by Valnea Scrinari on behalf of the Venetian Superintendence of Antiquities, brought to light only the southeastern corner of the building, at a depth of about 80 cm from ground level and covering an area of about 130 sq. m.

From these early investigations remain the notes and sketches that Giovanni Battista Brusin, archaeologist and director of the Archaeological Museum of Aquileia from 1922 to 1952, recorded in his diaries. Other limited surveys and restoration and conservation work on the structures were carried out in 2002 and 2008 by the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici del Friuli Venezia Giulia.

The size of the villa is currently unknown. Recent geoarchaeological investigations carried out in 2022 as part of the "E-VILLAE" project promoted by the Municipality of Staranzano have made it possible to identify, to the southeast of the already excavated complex, traces of at least two rooms probably pertaining to the villa but not physically connected to the residential part.

The first building of the complex is dated to the second half of the 1st century BC. Based on archaeological data, we know that between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD changes were made to the building during at least two phases of renovation.

The villa was inhabited until the beginning of the third century AD. Renovations involved not only changes in the size of the rooms, but also the use of different building materials in the masonry: the earliest phase saw the use of river pebbles, while in more recent ones brick fragments and tiles were also used. The latter were often stamped with trademarks referring to well-known local manufacturers.

The 1955 excavation brought to light three identical rooms, paved in opus caementicium (beaten mortar incorporating flakes of stones of different colors), placed side by side and facing a long and narrow room, perhaps a courtyard, referable to the first building phase.

During the first renovation, the room to the southeast (A) was considerably enlarged: one part was paved in terracotta cubes and the other in black and white tessellation; a black and white checkerboard mosaic (emblem) was inserted in the center of the room. This room was possibly used as a triclinium (dining room), with the triclinar beds probably arranged on the terracotta-paved area.

The northernmost room (C), now covered by a canopy, was also repaved with a white-tile mosaic framed by a black-tile band.

A black-and-white checkerboard pattern was inserted in the center of the floor, also bordered by a black frame.

The last renovation,characterized by a sloppy construction technique,made significant changes to the great hall (A).

Part of it was subdivided into four small rooms or cells by walls.

The discovery of a squared stone block with a central hole (D),juxtaposed to the perimeter wall of the housein correspondence with an external buttress, leads to the hypothesis that a post was inserted there to support a movable partition (e.g., a curtain): this would have allowed the room to be further divided, creating a sort of antechamber and preventing the view of the cells. Such elements suggest the transformation of this part of the villa into a sacellum, that is, a place intended for a domestic cult.

The room was entered from the courtyard through a door documented by the finding of a stone threshold (E) with hinge holes. This transformation into a sacellum is corroborated by the finding, in this room, of a large stone slab (dimensions preserved 57 x 57 cm), possibly a mensa, a kind of table for ritual offerings.

It bears engraved the inscription B(onae) D(eae) V(otum) / PETICIA L(uci) L(iberta) AR[-] testifying to the dissolution of a vow made by Peticia, a freedwoman (freed slave) of the Peticii family, to the Bona Dea.

The inscription is dated between the end of the first century B.C. and the first half of the first century A.D. and thus testifies that the cult to the Bona Dea was practiced in the Staranzano villa already during its first phase of establishment.

A large quadrangular platform was also found in the inner courtyard of the complex, paved with terracotta cubes, whose function or possible relationship to the sacellum is unknown.

The cult of Bona Deaera particularly widespread in the territory of Aquileia and was connoted as a mystery cult, practiced only by women, whose characters could not be known to men. Celebrations were held in public form in temples but also in private form inside homes; free women and enfranchised slaves participated.

The presence of the small cells in room A of the villa harkens back to sacred buildings dedicated aquesta deity salutifera, for example the temple of Bona Dea Subsaxana on the Aventine Hill in Rome or the one identified in the center of Trieste in 1910, where the cells were perhaps intended for the performance of divination activities or healing rites.

Understanding the architectural features of the Staranzano villa and reconstructing its phases of occupation are particularly problematic because of the paucity of everyday materials recovered during archaeological investigations, such as pottery and amphorae. Only stamped tiles and a few metal objects, such as a bronze net needle, are mentioned in the 1955 excavation diaries.

Roman villa in Staranzano: the first investigations

Fortuitously, the discovery of a mosaic floor in the Staranzano area, northeast of the built-up area of the parish church property, occurred.

Prompt reporting by the municipality meant that the Superintendence of Antiquities of the Venezie was able to intervene promptly to view the case. Under the diligent guidance of technical assistant G. Runcio the excavation was started and, by the agreement reached between the municipality the parish church and the neighboring landowner, Mr. E. Laurentic, was able to be expanded to an area of 128 square meters, at a constant depth of 0.80 meters from ground level.

The difficulty of the work was mainly due to the highly clayey soil and the goodness of the wine and fruit crops in the area, which elevated in no small measure the compensation to be paid and owners for the damage suffered.

The interest in the complex that has come to light, however, has afforded the work of the Superintendency the utmost solicitude and understanding on the part of the local authorities, who earnestly desire, to their credit, to be able to highlight and preserve in view what documents the ancient life of the place.

The labor therefore was made available by the City of Staranzano having sent there the Directorate of Excavations of Aquileia a skilled and skilled worker so that supervision over the earthworks would be constant.

Towards the end of May there was also an inspection by the Superintendent of Antiquities himself, Dr. B. Forlati, who was warmly pleased with the work in progress.

From what has now been brought to light, the visitor reports the impression of an interesting and lively Roman-age wall complex in its structures, its orderly topographical arrangement, and the simple elegance of its mosaics. And it is a discovery that is not surprising given the presence a short distance to the west of the Roman road that passed through the lower Monfalcone area, linking Aquileia to Tergeste, and the similar discoveries, of houses and works from the Roman period, that occurred in the area in earlier years.

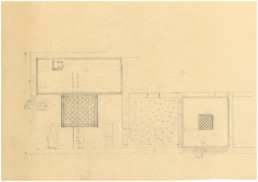

The excavation has currently uncovered the rooms that line the east side of the complex, it would remain to explore the west side with the connecting rooms in the south and north sides whose continuation is evident from the western clay embankment (fig.1).

Le strutture che si elevano dal terreno di base per un’altezza media di circa metri 0,50 si presentano di tre qualità diverse ed aiutano, insieme al livello e al tipo di pavimenti, a seguire la vicenda edilizia della casa. I muri che affiorano a profondità maggiore si presentano a ciottoli di fiume. La sezione normale di tali muretti a corsi regolari dà uno spessore medio di metri 0,45 e dimostra la loro erezione con circa quattro elementi collegati da malta biancastra di poca consistenza. La pianta della casa costruita a muri di ciottoli e in seguito ampliata da sul lato sud di circa quattro metri, ma nella fase prima, di cui ora parliamo, era costituita, nell’area scoperta almeno, poiché i muretti di ciottoli continuano sottoterra tanto verso Nord quanto verso Ovest, da tre vani (a, b, c) che si aprivano nell’interno verso un probabile corridoio (f). Il muro a ciottoli lungo il lato Est presenta all’esterno due piccoli contrafforti dello stesso suo tipo, disposti ad intervallo regolare dello spigolo Sud-Est della casa, rifiniti in modo da far pensare ad una loro funzione decorativa o strutturale connessa al muro perimetrale.

A sostegno, ad esempio, delle gronde di scolo del tetto. L’ampliamento della casa verso meridione con muri di tipo diverso riprende infatti il medesimo motivo del contrafforte sul lato Sud. Si noti che la distanza del contrafforte dallo spigolo a Sud Est è circa la stessa su tutti e due i lati. Questa equidistanza che riprende quella degli elementi aggettanti sul lato Est non può essere casuale (fig.2). L’ampliamento della casa avviene dunque come abbiamo or ora notato con struttura di tipo diverso: si reimpiegano i ciottoli risultanti dalla rovina di alcuni tratti dei muri precedenti e ad essi si aggiungono con poca malta gialliccia, più grassa, frammenti di tegole e mattoni sottili giallo chiari di fine argilla cotta in fornace, mantenendo un spessore medio di metri 0,45.

Rather than in the walls, where tile fragments predominate, bricks are encountered in abundance in the earth being quarried and are likely evidence of the regular brick row structure that the masonry on high ground will have had. It is interesting to note how an attempt is made to give the functional masonry a certain organicity, alternating rows of pebbles with rows of fragmented tiles, according to a rhythm present wherever the nearby river had provided building pebbles for the inhabitants.

See the monumental example offered by Turin's Porta Romana, which alternates between bright red brick and white cobblestones in an extremely painterly cadence.

The exterior of the wall added to the east and south testifies even more validly to the perimeter function of the cobblestone wall to the east and the rearmost wall to the south, as it is more solid than the interior walls and walks on a slightly overhanging base plinth. Also absent all around are attachments of other masonry or traces of pavement battens (fig.3).

Further variations in the internal plan of the complex, again related to the area brought to light, are brought by a third type of masonry, with an average thickness of half a meter built almost only with fragments of tiles joined by little thin, grayish mortar.

Whereas in the walls of the second phase the tile fragments were often arranged in a herringbone pattern with a tasteful decorative sense as well as practicality of use, in these walls of the third phase the tone is that of a structural arrangement that jumbles tiles and bricks with purely functional intent and much haste in execution (fig.4).

Representative of this phase are the three small walls built above the floor of compartment C in the east-west direction and the large quadrangular basement in the area of compartment D so far discovered to the south.

The third phase rather than expansions therefore seems to have brought internal additions resolved with reused material, taken from some old deposit because there are tiles and bricks of various types and stamps found there, prevailing, however, always the light-colored clay fine pulled form of thin thickness.

The most frequent stamps are thus already known in the area from the kilns of Q.CLODIUS AMBROSIUS, not that the more singular ones of B. VETTIA, ASSIANI and L. PET., impressed in the elements with different characters such as to demonstrate the development over time of production. Typical in this regard are the kiln stamps of Q. CLODIUS AMBROSIUS.

Regarding the levels and paving of the compartments we note that compartments B and C connected to and bounded by the older walls, present a beaten earth paving with inserted in picturesque disorder of fragments of beautiful green, gray, and red pebbles along with a few dark red terracotta flakes.

This type of floor, Pliny's classic "signinum," is admirably preserved here in Compartment B and continues to be in use in the later phases, while in Compartment C, which undergoes the expansion of the second phase and the modification of the third, the signinum is covered by the second phase floor of cubed and regular terracotta and regular tessellated bichrome, black-white with a central checkerboard emblem.

Room A is also covered with a similar tessellation with the small checkerboard in the center, while and all the other rooms have uniform and terracotta cube flooring (fig.4).

Il livello dei pavimenti tra la prima e la seconda fase quindi varia di qualche centimetro appena o non varia affatto (fig.5).

A sostegno, ad esempio, delle gronde di scolo del tetto. L’ampliamento della casa verso meridione con muri di tipo diverso riprende infatti il medesimo motivo del contrafforte sul lato Sud. Si noti che la distanza del contrafforte dallo spigolo a Sud Est è circa la stessa su tutti e due i lati. Questa equidistanza che riprende quella degli elementi aggettanti sul lato Est non può essere casuale (fig.2). L’ampliamento della casa avviene dunque come abbiamo or ora notato con struttura di tipo diverso: si reimpiegano i ciottoli risultanti dalla rovina di alcuni tratti dei muri precedenti e ad essi si aggiungono con poca malta gialliccia, più grassa, frammenti di tegole e mattoni sottili giallo chiari di fine argilla cotta in fornace, mantenendo un spessore medio di metri 0,45.

Rather than in the walls, where tile fragments predominate, bricks are encountered in abundance in the earth being quarried and are likely evidence of the regular brick row structure that the masonry on high ground will have had. It is interesting to note how an attempt is made to give the functional masonry a certain organicity, alternating rows of pebbles with rows of fragmented tiles, according to a rhythm present wherever the nearby river had provided building pebbles for the inhabitants.

See the monumental example offered by Turin's Porta Romana, which alternates between bright red brick and white cobblestones in an extremely painterly cadence.

The exterior of the wall added to the east and south testifies even more validly to the perimeter function of the cobblestone wall to the east and the rearmost wall to the south, as it is more solid than the interior walls and walks on a slightly overhanging base plinth. Also absent all around are attachments of other masonry or traces of pavement battens (fig.3).

Further variations in the internal plan of the complex, again related to the area brought to light, are brought by a third type of masonry, with an average thickness of half a meter built almost only with fragments of tiles joined by little thin, grayish mortar.

Whereas in the walls of the second phase the tile fragments were often arranged in a herringbone pattern with a tasteful decorative sense as well as practicality of use, in these walls of the third phase the tone is that of a structural arrangement that jumbles tiles and bricks with purely functional intent and much haste in execution (fig.4).

Representative of this phase are the three small walls built above the floor of compartment C in the east-west direction and the large quadrangular basement in the area of compartment D so far discovered to the south.

The third phase rather than expansions therefore seems to have brought internal additions resolved with reused material, taken from some old deposit because there are tiles and bricks of various types and stamps found there, prevailing, however, always the light-colored clay fine pulled form of thin thickness.

The most frequent stamps are thus already known in the area from the kilns of Q.CLODIUS AMBROSIUS, not that the more singular ones of B. VETTIA, ASSIANI and L. PET., impressed in the elements with different characters such as to demonstrate the development over time of production. Typical in this regard are the kiln stamps of Q. CLODIUS AMBROSIUS.

Regarding the levels and paving of the compartments we note that compartments B and C connected to and bounded by the older walls, present a beaten earth paving with inserted in picturesque disorder of fragments of beautiful green, gray, and red pebbles along with a few dark red terracotta flakes.

This type of floor, Pliny's classic "signinum," is admirably preserved here in Compartment B and continues to be in use in the later phases, while in Compartment C, which undergoes the expansion of the second phase and the modification of the third, the signinum is covered by the second phase floor of cubed and regular terracotta and regular tessellated bichrome, black-white with a central checkerboard emblem.

Room A is also covered with a similar tessellation with the small checkerboard in the center, while and all the other rooms have uniform and terracotta cube flooring (fig.4).

Il livello dei pavimenti tra la prima e la seconda fase quindi varia di qualche centimetro appena o non varia affatto (fig.5).

Interessante è notare i frammenti di intonaco che aderiscono ancora alle pareti est sud e ovest nel vano C e che si fondano sul tessellato pavimentale, dimostrando la precedenza del mosaico nell’ordine dell’esecuzione dei lavori nella casa e la contemporaneità del pavimento in cotto e del tassellato perfettamente suturati (fig 6).

Rare fragments of amphorae and vessels, lacking absolutely any kind of furnishings, the building faintly raises its voice from a single stone inscription.

Like the walls, the stone also shows that it was reworked and engraved in two different periods.

The type and that of a quadrangular platform fragment (57x57x0.90) that on its side bears the epigraph B.D.V. PETICIA LL AR. and on the surface the later inscription NIGELI almost barely graffitied. The stone was found in chamber c together with an in situ anchor without inscription but of roughly similar proportions (59x60x0.09) with a central hole in the surface.

At the current state of the excavation that I simply present here reserving further details when the excavation is completed to avoid errors of evaluation or interpretation so easy on the "surprise" terrain of 'Archaeology, it is possible to deduce the following: we are faced with a building whose origin by types of floor structures can be placed on the border and three first century B.C. and the first century A.D., which develops with extensions in plan and black-white geometric mosaic flooring around the second century A.D., taking on a particular appearance later.

The latter is given to it by the internal modifications that are not very canonical for the life of a simple rural villa, as the primitive appearance of the complex would make us call it typologically. In fact, if room c in its second phase suggests its probable distraction into a triclinium with the terracotta floor in the tricliniar bed area and the mosaic carpet the free area, in the third phase it is oddly divided into four small rooms proceeding above the terracotta floor (see fig. 1).

Why?

E quale è lo scopo del grosso basamento quadrangolare costruito in D pure sopra il pavimento in cotto (fig.7)?

Troppo grande per essere la base di un pilastro o di una colonna, il cubo rimane per ora a sé stante ed aspetta una soluzione nel procedere dello scavo verso Ovest. Ma l’iscrizione trovata apre una possibilità nuova di interpretazione: non potrebbe essere stato adibito ad un certo momento a sacello, a sala di culto privato o pubblico?

They might have been what horrendous description the initials B.D.V were surely read as B(ONAE) D(EAE) V(OTUM), interpreting the stone as the base of an element (labrum?) offered by Peticia, probable freedwoman of a Lucius, surname AR(RIANA?) as a vow to the Bona Dea, a well-known and honored deity of our region (compare the sacellum of Trieste and of the cult in Istria and Aquileia), especially by women precisely if freedwomen.

In this case, the north stone threshold, finished, high, with side holes for the hinges of the door-knockers, nor the special subdivisions of the eastern compartment that might have run as offering deposits or secret recesses of worship (the Bona Dea was often associated with high deities), nor some trace of transenna perhaps recognizable between the terracotta floor tiles and the tessellated, along their always perfect and stringent suture in the northern area, nor the stone basement in situ on the southern side, would be surprising.

But to validate our hypotheses we still have to wait until the earth has opened its every secret to us. In the meantime, we note that the gens PETICIA is well known in the X Regio Venezia et Histria through various inscriptions found in different places, providing good evidence of the spread of the family in the area.

Traces of fire, damage done to the floors by ruined material in the fall from above, document the little drama the building experienced perhaps as early as imperial times with the descent of barbarian prizes or opposing legions in the imperial struggles of the 3rd century.

The looting or flight of the inhabitants under the nightmare of danger meant that the best furnishings and what was salvageable were carried far away. This is perhaps why the excavation did not return anything that could tell us more about the men who animated with their existence the short stretch of space and time between the cobblestone and brick walls.

Valnea Scrinari

Valnea Scrinari è stata un’ archeologa triestina laureatasi dapprima a Trieste nel 1945 con il professor Mario Mirabella Roberti, di cui fu poi assistente, e poi a Roma, in Lettere classiche. Già Sovrintendente delle Venezie, si dedicò al Museo archeologico di Aquileia per passare successivamente alla Direzione della sovrintendenza alle antichità di Roma e poi di Ostia.